Viewpoints

The good shepherd

There is pain, but also a kind of comfort,

in easing a beloved pet’s passing

It is devastating to lose the assurance of times to come, but it can also be liberating to slow down and immerse ourselves in the now.

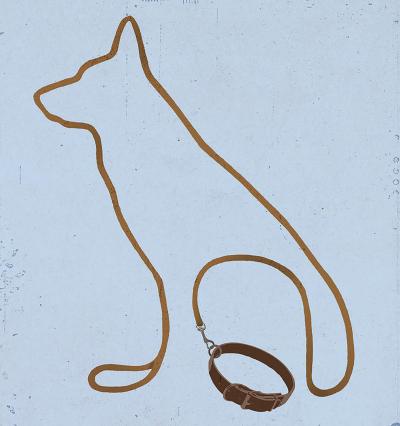

Image by Richard Mia

Our family recently said goodbye to our dog. I’ve loved many pets, but Ranger was my spirit animal. I used to tell friends that losing him would put a serious dent in my being. A 70-pound shepherd who dutifully tracked every family member’s whereabouts, he was a gentle creature. I adopted him when he was seven years old. Like many older dogs, he had spent far too much time in shelters, moving from state to state before ending up in a no-kill shelter in Chicago. He was missing teeth and afraid of feet and dark doorways. But with love and routine, he turned into a confident, calm keeper. His soulfulness radiated.

In his prime, he was valiant, and a bit foolhardy. One January morning as we played fetch on a snowy beach, he spotted two coyotes sauntering along a lakefront path and tried to herd them, occasionally looking at me over his shoulder as if to say, “Thanks for arranging this! Great fun!” Later he was subjected to two new feline family members who he initially seemed to think were chew toys that scurried for his entertainment. But he came to respect and even look out for them. He visited my mom, who is in her 80s, most weekends. She would invite him onto the couch and he would lay his head in her lap. They sat for hours like that, paw in hand. On walks in the city, he tilted his chin to the sky and howled along with passing sirens. The rest of us often joined in. He delighted us. He guided us. He was my example of how to be.

Many people have known this joy. Pets are often more integral to our daily rhythm and wellness than our human relatives. We know our animals’ favorite snacks and toys. We know what upsets their bellies, what sounds scare them, and which hip rub is just right. In many cases, the relationship is much more than animal companionship. It is friendship, acceptance, family, purpose. It’s a degree of loyalty and adoration that we may not experience with most humans. So when we see our four-legged friends suffering at the end of life, the knowledge that we can end their pain is both a relief and a terrible burden.

Ranger was probably in more pain than we realized. We were still playing for the long run, thinking we had a couple of years left. But it was the wrong timeline. I called a friend who had recently lost her chocolate Lab and told her that Ranger seemed to be winding down. We had been trying to arrange rehab, but new symptoms had emerged. “When you’re ready, say goodbye to him at home,” she advised. “That’s what we did.” She described her dog’s passing as beautiful — he was in his bed with the whole family beside him. “I’ll never forget that vet’s caring manner,” she said. We agreed that making the end of life as comforting as possible for our pet was as important as everything preceding it.

I contacted Amir Shanan, a veterinarian who founded the International Association for Animal Hospice and Palliative Care, a nonprofit whose mission is to address “the physical, psychological, and social needs of animals with chronic and life-limiting diseases,” and to provide support for their caregivers.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as an approach that “provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms … integrates the psychological and spiritual aspect of patient care; offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death”; and helps families cope. Perhaps most important, palliative care aims to “enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness.”

Although we tried a new approach to pain management with Shanan, we knew that euthanasia was our next step for Ranger. For some, this is not an acceptable option. For me, it feels intolerable to wait for an animal’s natural passing once I know that pain and suffering outweigh his comfort and joy. A domesticated dog is dependent on its human. Minimizing pain and distress is as much a part of my responsibilities as vaccines, nail trims, and heartworm prevention. Euthanasia is the ultimate decision. It requires compassion, and it creates anxiety.

These considerations can toss us into a chasm of anticipatory grief. We may begin to see each moment as sorrowful and worry about the risk of regret. Is it too soon, or too late? When Ranger was sick, I vacillated hourly. If he ate heartily, I thought he was going to recover. If he panted longer than usual, I feared I had waited too long and his pain was unbearable. A good palliative team helps pull back the lens and assess overall wellness, ability, and contentment. Our dog was not content. He could no longer do his shepherding. When we arrived home, his front paws drummed repeatedly in an effort to stand and greet us. But he could not raise himself.

Palliative care provides what is needed for comfort, which often is not another medical intervention. It focuses on the smallest pleasures, which tend to yield the greatest joy: eating a favorite food. Resting in a patch of sun. Petting a dog’s fur. It is devastating to lose the assurance of times to come, but it can also be liberating to slow down and immerse ourselves in the now. In her poem “A Note,” Wisława Szymborska wrote: “Life is the only way / to get covered in leaves, / catch your breath on sand, / rise on wings; / to be a dog, / or stroke its warm fur; / to tell pain / from everything it’s not; / to squeeze inside events, / dawdle in views, / to seek the least of all possible mistakes.”

Shanan explained that there is no perfect time to set a pet free. Rather, there’s a range, and we want to be within it. His perspective was invaluable. At his first visit, he spent over an hour with us, addressing our family’s distress as much as our dog’s. He asked if we were sleeping, and how we managed the stairs as we navigated a 70-pound dog in the sling we used to support his back legs.

Concerns about cost evaporated. Veterinary hospice helped us forgo unnecessary treatments as we focused on making Ranger comfortable. It was the right health care investment. I think of the money we spend on electronic gadgets or travel because we believe those things make our lives better or make us happy. Ranger fetched us immeasurable happiness. And saying goodbye to him in his favorite spot, where he knew he was safe, with his squeaky hedgehogs and us beside him, was the best version of a dreaded farewell.

We never have enough time with those we love. Ranger’s absence still hurts. For a month, vacuuming made me cry, because it was another bit of him gone. I think about him every day and channel his steady energy to help with our new endeavor, Lulu. She is a five-month-old pup we fostered, then adopted. Many people, including myself, ask why we got a puppy. I think it has to do with wanting more time. The five years I had with Ranger didn’t seem nearly enough, yet I know that part of the reason we bonded so quickly is that he was an older dog when we met. He had nothing to prove, except devotion. He was ready to relax.

Lulu’s intermittent hyperactivity makes me miss Ranger’s soulful ease. But she also helps me remember that life can expand after loss. Ranger was considered a problem dog at the shelter. He was vocal, and after weeks in a cage, he went on a hunger strike. But with us, he was a mellow, quiet gentleman who never skipped a meal. I suspect that with routine and love, Lulu will ease into a similar calm confidence that our old pal had. Now, Lulu takes 20 minutes to walk one block because she must investigate and marvel at everything. When we finally get back home, I congratulate her, just as on that last morning with Ranger, we again told him that he was a good dog and that he had done all his jobs well. The manner in which we chose to say goodbye helped us feel that we had done ours well, too. And then we let him off the leash.

• Shirley Stephenson is an advanced practice nurse and a regular contributor to The Rotarian.

• This story originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of The Rotarian magazine.