Rotarians Address Mental Health Issues Head On

Rotary has a remarkable record when it comes to health initiatives. We’ve helped bring polio to the brink of eradication, and clubs have carried out myriad projects focused on preventing disease and supporting maternal and child health. Now the global pandemic has brought attention to another aspect of health that is often overlooked: mental health. In many places, depression, anxiety, and suicide are seen as things to be ashamed of and kept quiet. But Rotary members are recognizing the gaps in understanding and resources and are stepping up to help.

More than 264 million people worldwide are affected by depression, according to the World Health Organization.

“A year ago, we had 50 members of the Rotary Action Group on Mental Health Initiatives,” says Bonnie Black, a member of the Rotary Club of Plattsburgh, New York, and the chair of the action group. “We’ve tripled our membership during the pandemic, and I believe it’s due to the heightened awareness of mental health and wellness.”

More than 264 million people worldwide are affected by depression, according to the World Health Organization, and although many mental health conditions can be effectively treated at relatively low cost, many people who need treatment do not receive it.

Felix-Kingsley Obialo, a member of the Rotary Club of Ibadan Idi-Ishin, Nigeria, manages the local arm of a project called Wellness in a Box, which his club has worked on in partnership with the Rotary Club of Wellesley, Massachusetts. “Mental health is an area that has been neglected by many people for too long because of the stigma associated with it,” says Obialo. “The involvement of Rotary clubs will gradually reduce the stigma, and more and more people will begin to be comfortable around the issue.”

Mental health is an area that has been neglected by many people for too long because of the stigma associated with it. The involvement of Rotary clubs will gradually reduce the stigma, and more and more people will begin to be comfortable around the issue.

Felix-Kingsley Obialo

Member of the Rotary Club of Ibadan Idi-Ishin, Nigeria, and Wellness in a Box manager

Refugees and migrants receive free access to mental health services in Germany

When Pia Skarabis-Querfeld saw refugees pouring into Germany to escape war and other atrocities in 2014, the Berlin-based doctor felt compelled to help. Skarabis-Querfeld, a member of the Rotary Club of Kleinmachnow, eventually launched a nonprofit called Medizin Hilft (Medicine Helps). With support from a Rotary Foundation global grant and clubs around the globe, the nearly all-volunteer organization donates thousands of hours of medical care to refugees and migrants each year.

But doctors in the group quickly noticed that in addition to needing care for physical ailments, about half of their patients had symptoms of psychological problems or psychiatric disorders, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and addiction. In 2020, the Rotary Club of Morehead City-Lookout, North Carolina, worked with Medizin Hilft to secure another global grant that allows the organization to offer free mental health services.

Under the guidance of Ulla Michels-Vermeulen, a psychologist who is also a member of the Kleinmachnow club, psychologists, psychiatrists, translators, and social workers help people like Fatma, a Syrian nurse who once treated bomb attack victims. When the situation became too dangerous in Syria, she left home. But fleeing was traumatic, explains Michels-Vermeulen.

It costs society a lot if we ignore these mental health problems. And it’s a human right to get support if you are ill.

Ulla Michels-Vermeulen

Psychologist and member of the Kleinmachnow club

While crossing the Mediterranean, Fatma watched several passengers drown before another vessel came to the rescue of their drifting boat. She spent time in a refugee camp, where people slept in tents, there were no doctors, and there was not enough to eat. She was sexually assaulted several times on the journey.

“Fatma has been accepted to stay [in Germany] and is going to school to learn German, but she is still getting counseling. She is suffering from nightmares, sleeplessness, concentration problems, and flashbacks,” Michels-Vermeulen says. “It costs society a lot if we ignore these mental health problems. And it’s a human right to get support if you are ill.”

Social media campaign strives to break the stigma of mental health

After Darren Hands invited speakers to talk about mental health at a District 1175 (England) conference a few years ago, he and other local Rotarians were inspired to do more. “It was very powerful, and afterwards we thought, ‘What can we as Rotarians do when it comes to mental health? We’re people of action but not mental health professionals. But surely there’s some-thing we can do to help,’” says Hands, president of the Rotary Club of Plympton.

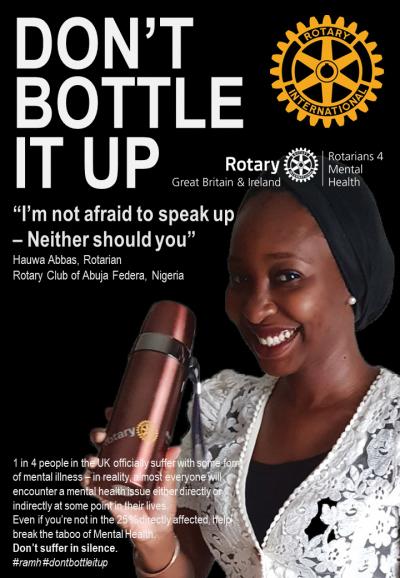

They came up with a social media campaign called “Don’t Bottle It Up,” which encourages people affected by depression, anxiety, or other issues to reach out for help. “The majority of people with mental health issues wait over a year to talk to someone,” explains Hands. “Hopefully we can help break down some of the stigma through this campaign.”

Darren Hands has made it easy for Rotary members to participate in the “Don’t Bottle It Up” campaign. “You simply take a photo of yourself holding a bottle and send it to me,” says Hands, who posts it on social media and adds local health statistics to make the message more relevant.

Launched in 2017 in District 1175, the campaign features local athletes and celebrities posing with a water bottle and the message “Don’t Bottle It Up.” The ads note that one in four people in the United Kingdom have some form of mental illness, and urge people not to suffer in silence.

Two years later, the initiative launched nationally in the UK and in Ireland. The group has a Facebook page and a website, and today 28 public figures and about 60 Rotarians have shared their image and message on social media.

“We have no direct way of knowing that the campaign has made a difference,” notes Hands. “But if just one person who has suicidal thoughts or is suffering from depression or anxiety sees one of these images and decides to seek help or at least talk to someone, to me, that will be a success.”

Wellness in a Box builds communities to rally around teens

The statistics on teenage suicide and depression are troubling — in the United States, suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15- to 19-year-olds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — and the global pandemic has meant that kids are more isolated than ever.

Wellness in a Box, the school-based mental health awareness campaign that Felix-Kingsley Obialo’s club supports in Nigeria, was started in 2013 by Bob Anthony, then a member of the Rotary Club of Wellesley, Massachusetts, at a local high school. The program has expanded to 20 schools in Nigeria, 18 in India, and three in Puerto Rico.

Through videos, workshops, and group discussions, Wellness in a Box presents information to students, parents, and teachers about depression and suicide, about activities to foster coping skills, and about how to seek help. Student leaders are taught to help lead a curriculum focused on preventing depression. The program promotes awareness, decreases stigma, and creates a network of teens and adults who can identify those who need help and refer them to professionals.

During a Wellness in a Box training session in Ibadan, Nigeria, Felix-Kingsley Obialo works with students on how to be peer leaders.

More than 264 million people worldwide are affected by depression.

Although there are effective treatments for mental disorders, between 76% and 85% of people in low- and middle-income countries receive no treatment for their condition.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds globally.

Depression and anxiety disorders cost the global economy $1 trillion per year.

There are 800,000 deaths per year from suicide.

Mental health conditions are especially common in populations affected by humanitarian crises.

Source: WHO

“We measured students’ knowledge of depression and their confidence in seeking help, and the numbers improved at all the sites — even more so when peers delivered the information,” says Anthony, who is now a member of the Rotary Club of Naples, Florida, and the treasurer of the mental health initiatives action group. In Nigeria, where mental health issues are especially stigmatized and rarely talked about publicly, “we’ve made people aware that treatment is possible,” Anthony says. In India, where some schools lacked counselors, the program publicized local hospital contacts whom people could go to for help and is paying for teachers to be trained in school counseling. “It starts with teens, but there’s a parent education workshop that every school is encouraged to provide,” he says. “Ideally, this is for everyone.”

Rotarians working on this project are hopeful that more clubs will focus on improving mental health. “Being a Rotarian confers a kind of legitimacy and authority on Rotarians in whatever they do,” says Obialo. “Rotarians thus become a moral force against the stigmatization of people with mental health conditions.”