How Rotary has changed to help people get clean water for longer than just a few years

The lack of access to clean water, sanitation facilities, and hygiene resources is one of the world’s biggest health problems — and one of the hardest to solve.

Rotary has worked for decades to provide people with clean water by digging wells, laying pipes, providing filters, and installing sinks and toilets. But the biggest challenge has come after the hardware is installed. Too often, projects succeeded at first but eventually failed.

Across all kinds of organizations, the cumulative cost of failed water systems in sub-Saharan Africa alone is estimated at $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion, according to data compiled by the consulting firm Improve International.

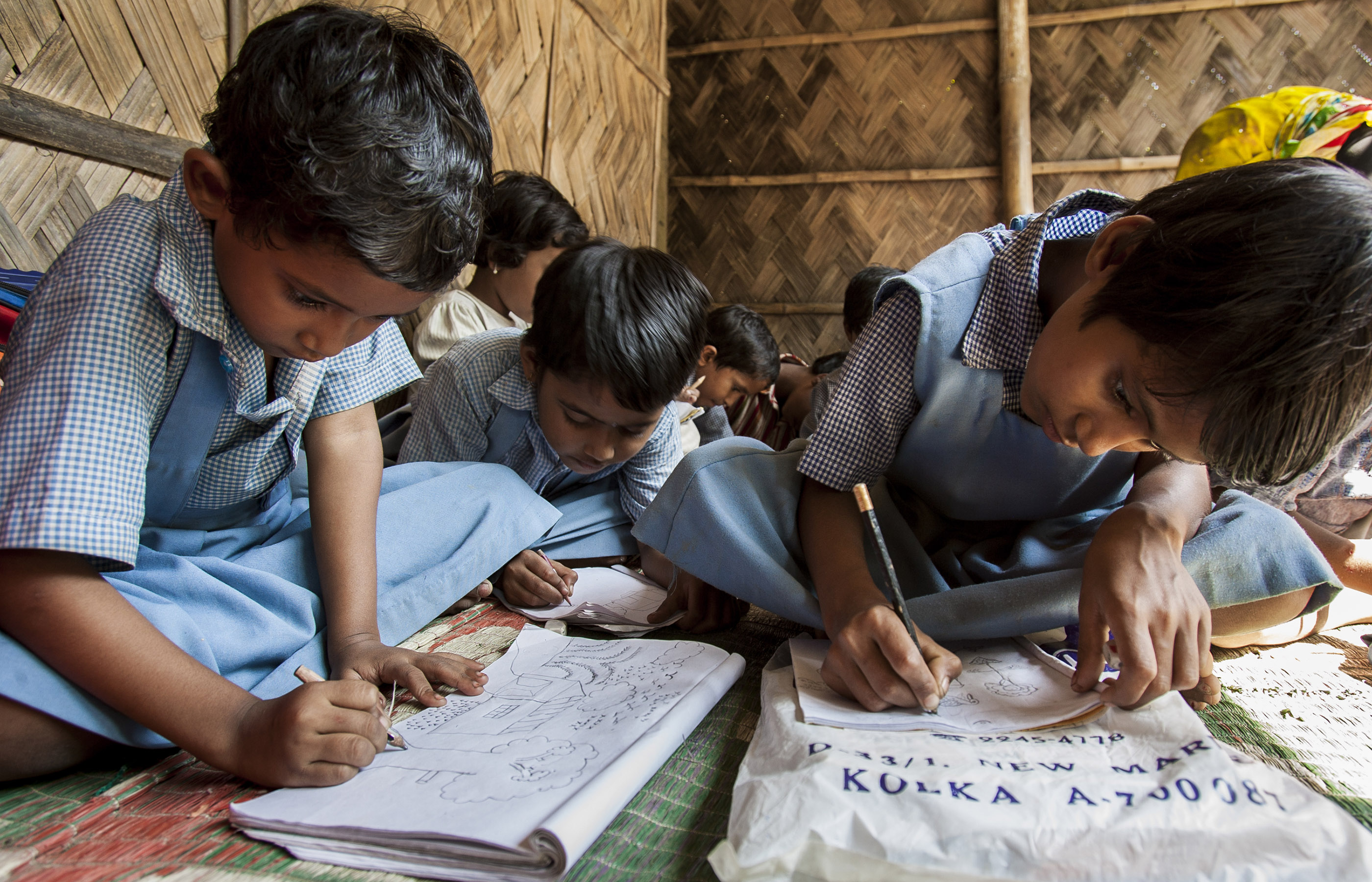

Rotary projects used to focus on building wells, but Rotary started to focused on hygiene education projects, which have a greater impact.

Rotary International

Rusted water pumps and dilapidated sanitation facilities are familiar sights in parts of Africa, South America, and South Asia — monuments to service projects that proved unsustainable. A 2013 review by independent contractor Aguaconsult cited these kinds of issues in projects Rotary carried out, and the review included a focus on sustainability to help plan more effective projects.

That’s one factor in why Rotary has shifted its focus over the past several years to emphasize education, collaboration, and sustainability.

With Rotary Foundation global grants, a dedicated Rotarian Action Group, and a partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Rotary’s water, sanitation, and hygiene, or WASH, programs are achieving greater, longer-lasting change.

“All Rotary water and sanitation projects are full of heart and well-intentioned, but many of them didn’t always meet the actual demands of the community,” says F. Ronald Denham, a founding member and chair emeritus of the Water and Sanitation Rotarian Action Group. The group, formed in 2007, stresses a needs-based approach and sustainability in projects.

In the past, equipment and facilities were usually installed properly and received well, but the local ownership, education, and sustainability were sometimes lacking. Communities often did not receive enough support to manage the projects independently for the long term.

One obstacle to sustainability: the ongoing human involvement that’s required.

Rotary members, by their nature, are volunteers. “Like everyone else, Rotarians have priorities like work and family,” says Denham, who has worked with clubs on water, sanitation, and hygiene issues for more than 30 years and led projects in Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Kenya, and Uganda.

Speaking of the Rotary members who work to make improvements in their own communities, he says, “It’s difficult for host clubs, for instance, to manage WASH projects long-term,” especially if the projects have complex technical components. “We’re extremely dedicated, but we need help. Reaching out is essential to our success.”

Community engagement, community ownership

That success now increasingly depends on collaborations with organizations that provide complementary resources, funding, technology, contacts, knowledge of a culture, and other expertise.

Rotary members work with local experts to make sure projects fit a local need and are sustainable. Educators Mark Adu-Anning, left, and John Kwame Antwi work with engineer Jonathan Nkrumah, center, Rotary member Vera Allotey, and Atekyem Chief Nana Dorman II on a sanitation projects in Ghana.

Photo by Awurra Adwoa Kye

“Clubs need to better engage with the community, its leaders, and professional organizations,” Denham says. “More important, we need to understand the needs of the community. We can’t assume or guess what’s in their best interest.”

The Rotary Foundation has learned over time that community engagement is crucial to making long-term change. It now requires clubs that apply for grants for some projects in other countries to show that local residents have helped develop the project plan.

The community should play a part in choosing which problems to address, thinking of the resources it has available, finding solutions, and making a long-term maintenance plan.

No project is successful, Denham says, unless the local community ultimately can run it.

In 2010, his club, the Rotary Club of Toronto Eglinton, Ontario, Canada, became the lead international partner in a water and sanitation program in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya, where clean water is scarce.

When initial groundwater tests revealed high levels of fluoride, the sponsor clubs changed their plan to dig shallow boreholes. Given what they learned, rainwater collection was a safer approach.

The Rotary Club of Nakuru, Kenya, the local host club, now provides materials and teaches families how to build their own 10,000-liter tanks. Each family is responsible for the labor and maintenance. With a $50 investment, a family can collect enough water to get through the dry season.

To date, the project has funded the construction of more than 3,000 tanks, bringing clean water to about 28,000 people. Family members no longer have to walk several miles per day to collect water, a task that often fell to women and children.

As owners of the tanks, women are empowered to reimagine how their households work. And with the help of microloans they get through the Rotary clubs, mothers are running small businesses and generating income instead of fetching water.

“With ownership comes liberation, not just for the mothers but for their children, who now have the time to attend school,” Denham explains.

Teaching WASH

It takes more than installing sanitation facilities for a WASH project to succeed in the long term. It’s also important to cultivate healthy habits. Good hygiene practices can reduce diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and pneumonia by nearly 50 percent. Washing hands with soap can save lives.

More than 4.5 billion people live without a safe toilet, the U.N. says. A lack of toilets leads to disease and also keeps some girls from going to school. In Ghana, Rotary and USAID projects at schools are leading to fewer days missed due to illness or menstruation.

Photo by Awurra Adwoa Kye

The Rotary Club of Box Hill Central, Victoria, Australia, facilitates Operation Toilets, a program that builds toilets and delivers WASH education to schools in developing countries including India and Ethiopia. The group constructs separate facilities for boys and girls to ensure privacy, and Rotary members teach students how to wash their hands with soap. Workers at each school are instructed in how to maintain the facilities.

The program works with the advocacy group We Can’t Wait, which raises awareness of WASH needs and promotes education to the community. Since the project launched in 2015, nearly 90 schools and more than 96,000 students have directly benefited from the program.

In another example of successful WASH education, the Rotary Club of Puchong Centennial, Malaysia, partners with Interact and Rotaract clubs in the Philippines to teach at several schools in Lampara, Philippines. The groups invited several speakers to instruct students about oral hygiene, hand washing, and the importance of frequent bathing. After each presentation, students were given kits that included toothbrushes, shampoo, soap, combs, and other toiletries.

10 years of sustainable WASH

This year marks the 10-year anniversary of the Rotary-USAID Partnership, which has brought communities and resources together to provide clean water, sanitation facilities, and hygiene education in developing countries. Rotary and USAID, the world’s largest governmental aid agency, bring distinct strengths to the effort. Rotary activates a global network to raise money, rally volunteers, and oversee construction, while USAID provides technical support to design and carry out the initiatives and build the capacity of local agencies to operate and maintain the systems.

Rotary-USAID education programs are teaching students in Ghana, like Philomina Okyere how to effectively wash her hands. More than 35 Rotary clubs are working in partnership on WASH projects in Ghana. Learn more about how our projects in Ghana will help 75,000 people in our interactive graphic.

Photo by Awurra Adwoa Kye

“Rotary brings a lot of energy to the program and has the ability to create a lot of buzz,” says Ryan Mahoney, a WASH and environmental health adviser for USAID and member of the Rotary-USAID steering committee. “They have been great at leveraging their relationships with community leaders to get projects off the ground.”

In Ghana, which was a focal point when the alliance launched, 35 Rotary clubs across six regions will have implemented more than 200 sustainable WASH programs by 2020.

Fredrick Muyodi and Alasdair Macleod, members of The Rotary Foundation Cadre of Technical Advisers, visited 30 of them last September to assess and evaluate their successes and ongoing challenges.

Macleod, a member of the Rotary Club of Monifieth & District, Tayside, Scotland, was impressed with the education efforts he saw. Most of the schools he visited had built-in education components, including a dedicated WASH educator on staff. In one case, the WASH teacher and students made and distributed posters about the importance of hand washing.

“Long-term projects need to start with the younger generation,” says Macleod. He adds that students can be agents of change in their own homes and in their communities by teaching the proper technique.

Other site visits revealed unexpected challenges, such as security. When a school has sanitation resources that are otherwise unavailable in a community, for example, the risk of break-ins and vandalism increases. Muyodi, a member of the Rotary Club of Kampala City-Makerere, Uganda, says that projects can lessen the risk by expanding to include the surrounding community.

Distance is also sometimes a challenge, if project sites are too far away for the clubs involved to commit to regular site visits. To remedy this, Muyodi says, clubs should engage with more local residents and create better links with leaders on the community and district levels.

Denham, a member of the Rotary-USAID steering committee, attributes the alliance’s success in Ghana to better coordination and communication, from using WhatsApp to connect with partners to hiring full-time staff. As it enters its second phase, the partnership — a landmark public/private collaboration in the WASH field — has secured $4 million in commitments for projects in Ghana, Madagascar, and Uganda. Rotary clubs in each country are responsible for raising $200,000.

“Rotary is in the business of social and economic development,” says Denham. “Our work in WASH can be a testament to that.”

Learn more about clean water

- Rotary-USAID partner page

- Overview of all Rotary’s water causes

- Rotary’s WASH in Schools target challenge

- UN’s World Water Day

Help us provide more clean water